Blog from Citizens' Inquiry into the Health of the Darling River and Menindee Lakes - 24 March, 2019

Our first week of Public Hearings, in Mildura/Buronga, Wentworth and Broken Hill--as part of the Citizens' Inquiry into the Health of the Darling River and Menindee Lakes--have been heartbreaking. We listened to people tell us about their dying ecosystems, stressed communities and fearful futures. But I must confess that none of it prepared me for the genuine shock of what’s going on in Menindee, and how life is there now for the 500 or so people who call this little town their home.

Menindee has been described as “ground zero” of the Darling River crisis. For the past 4 months, this small Australian outback community has had no drinking water. Water has been trucked in every week from Melbourne, or Adelaide; water that’s being donated by other Australian people.

I’ve visited other places in Australia with water shortages, or where the tap water didn’t taste great – but I’ve never been in a town in Australia where people can’t drink the water and are genuinely afraid of even touching it. It was a really strange and scary experience.

Up until November 2018, Menindee had a variable but reliable supply of fresh water from the Darling River, stored in weirs. Everyone has told us that even in past droughts, there was always water to drink. They have never run out of drinking water before. But this time, it’s been different. This time, the water left pooled in weirs is green and toxic with blue-green algae, and the locals can’t drink the water that’s being pumped from the weir into their homes.

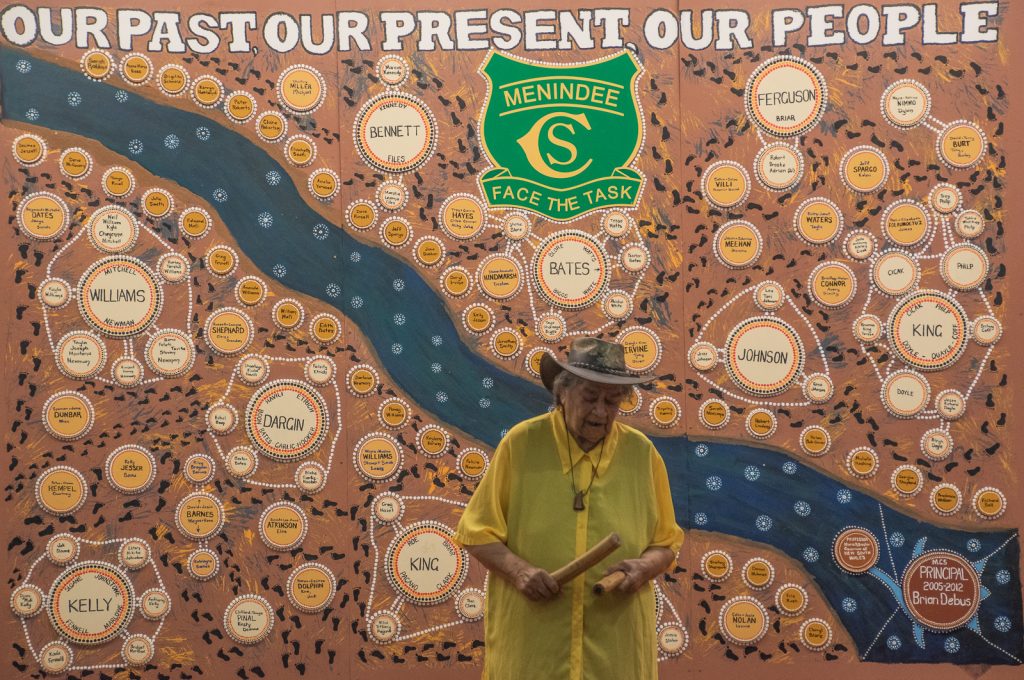

Aunty Beryl Carmichael, a Ngiyaampaa First Nations Elder, welcomed us to country, then spoke about how life used to be in Menindee, when the lakes had water in them. The town would swell to a few thousand, as people from other inland towns would come and holiday at the lakes, to swim, fish, camp and enjoy the cool waters. The abundance of animal life was astonishing – numerous types of native fish thriving in the lakes, different types of mussels, huge yabbies, and literally thousands of birds. A local fisherman told us that there was a time when the lakes were so full of fish that a thriving local commercial fishing industry operated from Menindee. It’s near impossible to imagine today.

When you stand on the edge of the lake beds at Menindee now, all you see is a dust bowl. No birds, no roos – and of course, definitely no fish, yabbies or other aquatic critters. The lake beds are massive, and the little community of Sunset Strip, a few rows of houses that used to once look out over the lakes, are now lined up looking over a sea of dust.

Australian communities and ecosystems are used to the cycles of drought and flood, but this town and its ecosystems aren’t just experiencing a dry patch – it looks and feels sick. The few kangaroos we saw coming into town were slow moving and sickly. There were no emus on the drive in, and no birdsong at sunset. Just silence.

Our Public Hearing, held at the local school, was well attended. One of the most disturbing stories shared by people, is the ‘cluster’ of cases of motor-neurone disease that have emerged only in the past few years. One woman told us how, over the past four years, she has lost two close friends after they contracted the disease and died within two years of their diagnosis. She had cared for them and fed them until they died. Others talked about reports linking blue-green algae in the water supply, to motor neurone disease.

People expressed their anger about the decision made by the State Government to empty the lakes after the last two big flows that had come down from the north, in the past few years. They said that if they’d just left some water in the lakes, instead of “releasing it all to the south, to the sea” then they wouldn’t be in the terrible position they were in now. They would have had enough water to make it to the next big flow. Everyone we spoke to expressed anger about “government mismanagement of the Darling River”, and their decision to empty the lakes without any consultation with local people. Throughout the day, we heard similar sentiments: “We’re never consulted”, “they don’t listen to us”, “we don’t matter”.

Aunty Beryl grew distraught as she talked about the toxic water that was now in the weirs. “We can’t drink the water, we can’t wash in it, everything’s dead – I keep thinking, what world am I living in? What world am I living in? Nothing makes sense.”

Farmers from out of town talked about how they have to buy water for stock, and wild animals won’t drink from the pools of water in the Darling River, they’ll only come and drink water from rain water tanks or clean water put out in containers for them. We heard stories about people losing dogs who drank the water and died, the loss of local businesses and the decline in the mental and physical health of local people.

Two B-double tankers of donated fresh water arrive in Menindee, Sunday March 24th, 2019. Photo: James K Lee

As people told us their stories, there was something in their eyes that was really upsetting, and I keep thinking about it. They were angry, sure, but what I kept seeing in their faces was a genuine, hurt bewilderment that this could be happening to them, their families, their communities, here in Australia.

On Sunday morning, before we left Menindee, we waited with some locals for the water trucks to arrive. It was surreal, as an Australian, to see other Australians standing around, waiting for drinking water to be delivered. As I walked back to our car, a cheerful old gentleman zoomed past in his mobility scooter, singing loudly and calling out his hellos. As he went past us, there was a sign on the back of his scooter “Let the river run”.

I laughed, and then cried. Yes, please, let the river run.